2011-2012 SEASON

Michelangelo Antonioni's The Passenger (1975)

7:00pm, Thursday, May 17, 2012

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A | 126 mins | English | Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

A melancholy, depressed and jaded television reporter assumes the identity of a dead man while at a hotel in a north African country, not knowing that the man was a renowned arms smuggler. The newsman sees this switch as a last desperate chance to escape his old life and start anew. However, as he begins to take on the characteristics of his new persona and understand his shady involvements, the decision becomes a risky one, which leads to an inevitable showdown.

"It's a movie from the past that still points ahead to the future: a cinematic rite of passage that raptly recalls a time when the world may have been as uncertain as now, but the movies were often lovelier and more daring." -Michael Wilmington, Chicago Tribune, 2005

"The Passenger is a marvel of quiet insight in many ways, not least of which is the chance to view Jack Nicholson before he became JACK NICHOLSON." -Peter Howell, Toronto Star, 2006

Nuri Bilge Ceylan's Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011)

6:45pm, Thursday, April 19, 2012

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

150 mins | Turkish with English subtitles | Colour | 2.35:1 | Blu-ray

In the dead of night, a group of men—among them, a police commissioner, a prosecutor, a doctor and a murder suspect—drive through the Anatolian countryside, the serpentine roads and rolling hills lit only by the headlights of their cars. They are searching for a corpse, the victim of a brutal murder. The suspect, who claims he was drunk, can't remember where he buried the body. As night wears on, details about the murder emerge and the investigators own secrets come to light. In the Anatolian steppes nothing is what it seems; and when the body is found, the real questions begin.

This masterful, radically revisionist take on the police procedural from acclaimed director Nuri Bilge Ceylan won the Grand Prix at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival.

"It is epic in its aims and achievements yet modest in its resources: some superb actors, stunning landscapes and a resonant, understated script." -Colin Covert, Minneapolis Star Tribune, 2012

"A gorgeously shot crime story with emotionally layered characters and an indelible atmosphere of unease." -Liam Lacey, Globe and Mail, 2012

"Turn the movie this way, and it's a police procedural that's tragicomically heavy on minutiae while slyly suggesting that official evidence always lies. Turn it that way, and it's an existential fairy tale set in a nocturnal netherworld." -Ella Taylor, NPR

R.W. Fassbinder's Lola (1981)

7:00pm, Thursday, April 12, 2012

12:00pm, Saturday, April 7, 2012

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

113 mins | German with English subtitles | Colour | 1.66:1 | 35mm

Part of Rainer Werner Fassbinder's The Entire History of the German Federal Republic trilogy, Lola stars Barbara Sukowa in the title role, a seductive cabaret singer and dancer in the 1950s who is romantically involved with Von Bohm (Armin Mueller-Stahl), a straight-as-an-arrow building inspector. Recently appointed Building Commissioner, Von Bohm is committed to eradicating corruption. Consequently, he's given quite a shock when he is called into inspect the brothel where Lola works and discovers her dancing there. With that, Von Bohm is left to question whether he is more loyal to the woman he loves so passionately or the career he believes in so strongly. The other entries in the trilogy are Veronika Voss and The Marriage of Maria Braun. -Matthew Tobey, Rovi

"Again Fassbinder returns to Germany's past to reveal the workings of its stagnant moral present to powerful effect, boldly combining melodramatic storytelling, vibrant performances, garish visuals and searching analysis." -Tom Dawson, Film4, 2004

"It's wonderfully provocative as only Fassbinder can be." -Dennis Schwartz, 2006

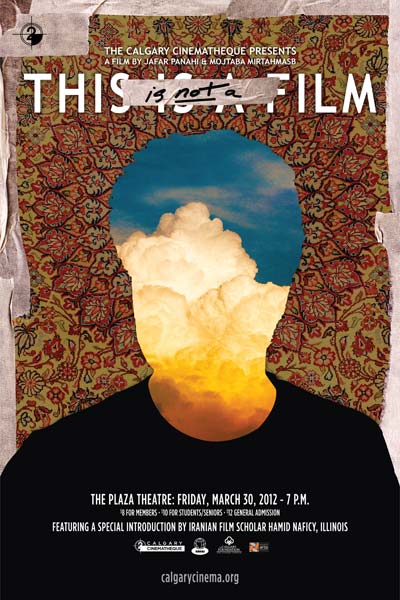

Mojtaba Mirtahmasb/Jafar Panahi's This Is Not A Film aka In film nist (2010)

7:00pm, Friday, March 30, 2012›

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

75 mins | Persian with English subtitles | Colour | DigiBeta

Film introduction by Iranian film scholar Hamid Naficy, Northwestern University, Illinois.

"It is not a protest; it is a plea. This is not a filmmaker who is a threat to his country; this is a national—and international—treasure." -Simon Miraudo, Quickflix

Jafar Panahi, the fifty-one-year-old Iranian film director, is a maker of nonpolitical films. Nevertheless, he has been sentenced by the Iranian authorities to six years in prison, and has been banned from directing, writing screenplays, or giving interviews for twenty years. His crimes are plain enough: he has been an outspoken critic of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. This Is Not a Film is a fable about a man who is free in spirit—an irrepressible director who will make films in his head if he has to. The movie is also about a man without fear. It is often funny and stirring, but as you are watching you know what the game will lead to; dictatorships are not known for their sense of humor.

The entire movie is an expression of freedom, and, as you watch it, you sense it will lead to more trouble for both Panahi and his friend (and it did: Mirtahmasb was jailed for three months and is currently out on bail). -David Denby, The New Yorker

The Calgary Cinematheque—in conjunction with the University of Calgary Film Society—are excited to be hosting esteemed Iranian film scholar Hamid Naficy. Professor Naficy is the Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al-Thani Professor in Communications at Northwestern University, Illinois, and will be introducing our one-night-only screening of This is Not a Film at the Plaza.

What's more, he'll be giving a talk on campus on March 30th—time and location TBA. This talk coincides with the UofC Film Society's weekly screening of 3 Iranian films leading up to this event—one for each Friday in March. More details on these FREE screenings are available on the Facebook event page.

Partner

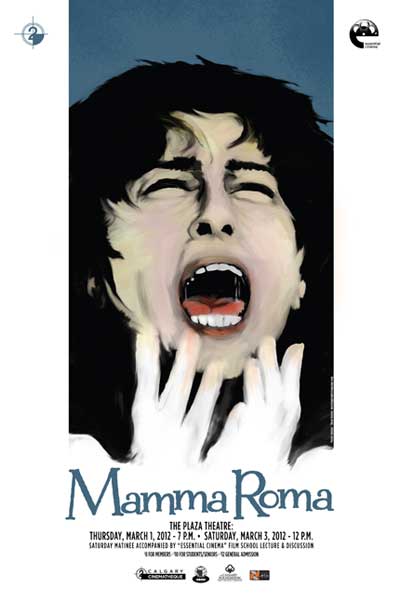

Pier Paolo Pasolini's Mamma Roma (1962)

7:00pm, Thursday, March 1, 2012

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

110 mins | Italian with English subtitles | B&W | 1.85:1 | 35mm

12:00pm, Saturday, March 3, 2012

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

Anna Magnani stars as Mamma Roma, a rural Italian hooker trying to create a new life for herself. This proves impossible when the past keeps rearing its ugly head in the form of Mamma Rosa's previous "johns." She returns to her old profession, whereupon her son Ettore Garofalo becomes a thief and is killed by the police. Written and directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini (his second film), Mamma Roma is one of the least known but most approachable of the director's efforts. As in many of his earliest movies (and the novels which preceded them), Pasolini explores the limited lives and dashed hopes of the cafoni, the Italian equivalent of America's hillbillies. -Hal Erickson, Rovi

"Draws from the neo-realist tradition, but Pasolini goes beyond the tradition to play with the form and structure." -Sean Axmaker, TCM

"A key transitional work for the cinematic subversive." -David Fear, Time Out

"The highlights are … exhilarating, free-wheeling cinematic moments without close parallels anywhere." -Jake Euker, FilmCritic.com

Luis Buñuel's Belle de Jour (1967)

12:00pm, Saturday, February 4, 2012

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A - Sexual Content | 101 mins | French,Spanish,Mongolian | Colour | 1.66:1 | 35mm

7:00pm, Thursday, February 9, 2012

Film School lecture & discussion will be hosted by Dr. Rebecca Sullivan, Dept. of English, University of Calgary.

Please note that due to scheduling conflicts, this month's Film School screenings will be in reverse order, of sorts. That is, the first screening—the Saturday matinee, this month—will feature our guest speaker, while the Thursday following will be a repeat screening for those who can't make it on the weekend.

Catherine Deneuve's porcelain perfection hides a cracked interior in one of the actress's most iconic roles: Séverine, a Paris housewife who begins secretly spending her afternoon hours working in a bordello. This surreal and erotic late-sixties daydream from provocateur for the ages Luis Buñuel is an examination of desire and fetishistic pleasure (its characters' and its viewers'), as well as a gently absurdist take on contemporary social mores and class divisions. Fantasy and reality commingle in this burst of cinematic transgression, which was one of Buñuel's biggest hits.

For people who find pleasure in sexual kinks but aren't quite comfortable with their appetites, Luis Buñuel's Belle de Jour is the ultimate candy. Perversely funny, and told in a manner that's elegant and nonjudgmental, Belle de Jour gives depravity a touch of class—and lets its audience indulge their guilty pleasures with impunity. -Edward Guthman, San Fransisco Chronicle, 1995

Luis Buñuel's particular combination of religion, decay, and morbid eroticism has never been my absolutely favorite kind of cinema—although Viridiana was great, and people who say they have an interest in the arts, "if only the subject matter were not so depressing," are of a particularly philistine order of square. But Belle de Jour is a really beautiful movie, and somehow, letting the color in—this is Buñuel's first color film—has changed the emotional quality of his obsessions in a completely unpredictable way. All these clean, lovely, well-dressed people preparing for their unspeakable practices are very attractive. -Renata Adler, NYT, 1968

Recently, there have been a slew of productions probing issues of identity and double lives. Indeed, this has become a favorite province of independent film makers, probably because it's such a rich field. However, back in 1967, the path was less frequently trodden, and Luis Buñuel's serious-yet-satirical picture helped pave the way for many stories yet to come.

Today, Belle de Jour is as effective as ever. With a ravishing Catherine Deneuve in the title role, this film is a study of contrasts. The main character is at once glacial yet erotic—a wife by night and prostitute by day. She is two different people in one body, but Buñuel underlines the truth that no person can effectively compartmentalize facets of their life. Crossovers are inevitable, and the harder we try to repress one segment of who we are, the more likely it is to assert itself—forcefully.

Buñuel also pokes fun at the morals of society by depicting what goes on behind closed doors at the brothel where Deneuve's Severine spends her afternoons. An internationally-known gynecologist begs to be punished. A businessman frolics with three girls at one time. Then there are Severine's erotic fantasies, which easily become entangled with her surreal secondary life. In fact, her misguided relationship with a gangster (Pierre Clementi) arises out of a hidden desire to flirt with danger.

All along, Severine's husband Pierre (Jean Sorel) is blissfully ignorant of his wife's daytime job. He loves her, but wishes she would be more sexually attentive. Meanwhile, a friend (Michel Piccoli) pursues Severine tirelessly—until he learns her secret. At that point, the chase loses its allure. After all, where's the fun if the "forbidden fruit" isn't quite so forbidden?

Much of the film works because of the capable acting of Deneuve. The scenes where she first approaches the brothel, tentative and uncertain yet undeniably intrigued, are perfectly realized. Deneuve's performance allows the viewer to feel—not merely sense—the strange mixture of seduction and repulsion that prostitution holds for a woman in her position. And, as Severine's sexual liberation takes place, Deneuve's beauty is transformed from cool and aloof to coy and playful. -James Berardinelli, 1995

Douglas Sirk's All That Heaven Allows (1955)

5:00pm, Sunday, January 29, 2012

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG | 89 mins | English | Colour | 1.85:1 | 35mm

"A masterpiece (1955) by one of the most inventive and recondite directors ever to work in Hollywood, Douglas Sirk." -Dave Kehr, The Chicago Reader, 2004

Jane Wyman is a repressed wealthy widow and Rock Hudson is the hunky Thoreau-following gardener who loves her in Douglas Sirk's heartbreakingly beautiful indictment of 1950s small-town America. Sirk utilizes expressionist colors, reflective surfaces, and frames-within-frames to convey the loneliness and isolation of a matriarch trapped by the snobbery of her children and the gossip of her social-climbing country club chums.

Douglas Sirk once said: "This is the dialectic—there is a very short distance between high art and trash, and trash that contains an element of craziness is by this very quality nearer to art." When All That Heaven Allows was released by Universal Studios in 1955 it was just another critically unnoticed Hollywood genre product designed to appeal to the trashy "women's weepie" audience. Now, in retrospect, it is considered to be closer to the art side of Sirk's "dialectic" and one of his key films. But this is part of a wider process of critical re-evaluation, in which his entire body of work has been rediscovered and reappraised by successive generations of filmmakers and historians.

No one seeing the film at the time would have imagined its director to be an elegant, extremely erudite European whose career started in the theatre of Weimar Germany and was an early director of Brecht's Threepenny Opera. After a short, but successful, career at the UFa studios in the vacuum left by the massive emigration of Jewish talent after the Nazis came to power in 1933, he made his way to Hollywood, directing his first film there in 1942. But after an unsuccessful attempt to return to Germany in 1949–50, he signed a contract with Universal Pictures. His movie career then culminated with his most high-profile films, the melodramas of 1952–58. By 1959 he was Universal's most successful director. At that very point, he left moviemaking and America. Until his death in 1987, he and his wife Hilde lived in Lugano, Switzerland.

All That Heaven Allows marks the final turning point in Sirk's strange and varied career. On the back of Magnificent Obsession's success the previous year, Universal gave him the budgets and the freedom that enabled his mature style to blossom. All That Heaven Allows contains all the elements of characteristically Sirkian composition: light, shade, color, and camera angles combine with his trademark use of mirrors to break up the surface of the screen. Here are all the components of the "melodramatic" style on which Sirk's critical reputation is based and that has made him the favorite of later generations of filmmakers, from Rainer Werner Fassbinder to Quentin Tarantino, from John Waters to Pedro Almódovar.

But at the time, Universal was anxious to repeat their successful pairing of Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson in a romance between an older woman and an extremely handsome younger man. Wyman was still a big star but, by then, past her prime. Recently divorced from Ronald Reagan, and aware that her future lay with the soap-opera audience, she was pleased to be teamed with Hudson. At the time, he was the new Hollywood heartthrob who, although "out of the closet" in his personal life, had to be continually shut back in publicly and professionally by an anxious studio.

The All That Heaven Allows version of the May-September romance formula has Wyman playing Cary, a well-to-do widow with two college-age children and a dull social life at the country club. The emptiness at the heart of her life is filled when she meets Ron Kirby, the young gardener-turned-tree farmer who prunes the trees that line her all-American suburban home - and then comes back to court her. This simple love story is disrupted by the vicious snobbery of her children and high society acquaintances. Early in the film, Cary is at her dressing table preparing for an evening at the Stoningham elite. To one side stands a vase containing the branches Ron had cut for her earlier, so that Cary's awakening interest in him carries over from the previous sequence. In a beautifully composed shot, the children first appear reflected in the mirror, coming between Cary and the vase, and, as the camera pulls away, she is taken back into the room and towards the children. This one shot tells the story of the dilemma that Cary will face for the rest of the film and is typical of Sirk's emblematic, economical use of cinema. His stars' performances mesh well with this style. He gives them the screen space appropriate for their status, but the sexual charge between Cary and Ron is articulated through looks and gestures, and the rollercoaster highs and lows of their love are displaced onto the things that surround them.

Objects play their own significant part in expressing the emotions blocked by convention in small-town, middle-class 1950s America. Sirk creates a cinema in which the screen itself speaks more articulately than its protagonists, tongue-tied by the conventions of their fictional setting, the powers of censorship in Hollywood at the time, and the norms of the family melodrama genre. Out of these constraints Sirk builds his film, also using a typically melodramatic score to punctuate points and to accompany the tones and textures of the actors' voices.

Years after initial dismissal (and sometimes derision) by reviewers, Sirk's successful string of big-budget soapers (and the director himself) acquired a rich and complex critical afterlife, as different aspects and facets of the films have been reclaimed by successive phases of film criticism. For auteurists and structuralists of the 1960s, Sirk's mastery of cinematic language transcended the working conditions of the Hollywood studio system; feminists reclaimed him as a director of melodrama, with his women protagonists and dramas of interiority, domestic space and sexual desire; gay critics today see a camp subtext in his films with Rock Hudson, in which double entendre and ambiguous situations can be read as something other than what they seem.

The gap between the contemporary perception of All That Heaven Allows and that of the later critics is closed by Sirk himself, who explained the conditions of work at the studio. "At least I was allowed to work on the material, so that I restructured to some extent the rather impossible scripts of the films I had to direct. Of course, I had to play by the rules, avoid experiments, stick to family fare, have 'happy endings' and so on. Universal didn't interfere with either my camera work or my cutting, which meant a lot to me." Although All That Heaven Allows does, on the face of it, have a happy ending, its "happiness" is twisted with more than a touch of characteristically Sirkian irony. -Laura Mulvey, The Criterion Collection, 2001

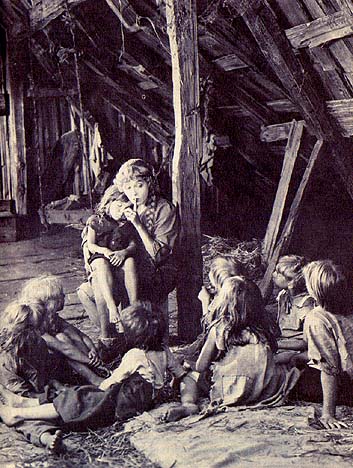

William Beaudine's Sparrows (1926)

7:00pm, Thursday, January 19, 2012

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG | 84 mins | English | B&W | 1.33:1 | 35mm

"The finest film of Pickford's entire career. A beautifully atmospheric horror masterpiece." -Elliott Stein, Village Voice

The choice of Sparrows was a singular one for Mary Pickford to make, but no one can deny that she has done the picture surpassingly well. The subject is gloomy, and some of the horrors recall Dickens, yet the darkness is shot through with many laughs. [Mary] is Mama Mollie, a lovely waif in whom the maternal instinct is well, there aren't words to tell how strong it is, for she mothers eleven woebegone, poverty-stricken children at a baby farm kept by the villainous Grimes in the midst of a Louisiana swamp. A kidnapped baby is thrust by Grimes into the group and the plot gets underway, Mollie's heroic efforts to keep the baby against the will of Grimes leading her and the entire brood into the deadly swamp. Sparrows is well worth seeing. -Picture Play, 1927

"So many on the screen can be the grand lady. And no one else that we have ever heard about or seen captures the elusive and misty quality of childhood as Mary does. You'll weep a little. You'll laugh a great deal. And you'll hold your breath once or twice." -Motion Picture Magazine, 1925

Ingmar Bergman's Wild Strawberries aka Smultronstället (1957)

7:00pm, Thursday, January 5, 2012

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

91 mins | Swedish with English subtitles | B&W | 1.37:1 | 35mm

12:00pm, Saturday, January 7, 2012

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

"An archetypal Ingmar Bergman film, and one of his best." -Dave Kehr, Chicago Reader, 2007

One of Bergman's warmest, and therefore finest films, this concerns an elderly academic - grouchy, introverted, dried up emotionally - who makes a journey to collect a university award, and en route relives his past by means of dreams, imagination, and encounters with others. … It's filled with richly observed characters and a real feeling for the joys of nature and youth. And Sjöström - himself a celebrated director, best known for his silent work (which included the Hollywood masterpiece The Wind) - gives an astonishingly moving performance as the aged professor. As Bergman himself wrote of his performance in the closing moments: "His face shone with secretive light, as if reflected from another reality … It was like a miracle." -Geoff Andrew, Time Out, 2006

The doctor's memory, involving wild strawberries, becomes one of the most memorable scenes in the film. It sharpens his awareness that somewhere along the way he has lost sight of the ideals of his youth. The wild strawberries remind him of the simple joys of life which he has neglected in favor of intellectual pursuits.

The idea for the film came to Bergman after a predawn drive on the E 4, as he traveled north from Stockholm to Dalarna. When he passed his hometown of Uppsala, he was overcome with a desire to stop and see his grandmother's home. As he walked into the house, he asked himself "What if I could suddenly walk into my childhood?" -Emenuel Levy, 2007

"Wild Strawberries deals with more human concerns [than The Seventh Seal] and does so with extraordinary beauty and grace." -Jeffrey M. Anderson, Combustible Celluloid, 2002

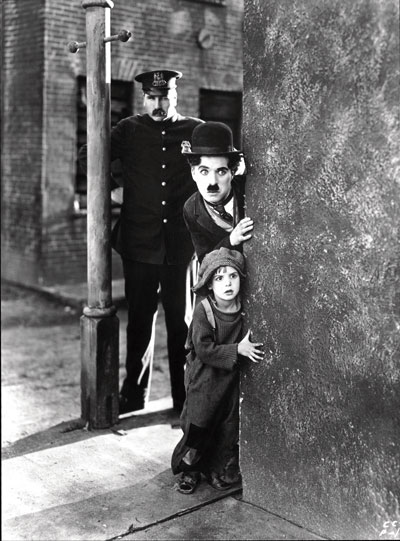

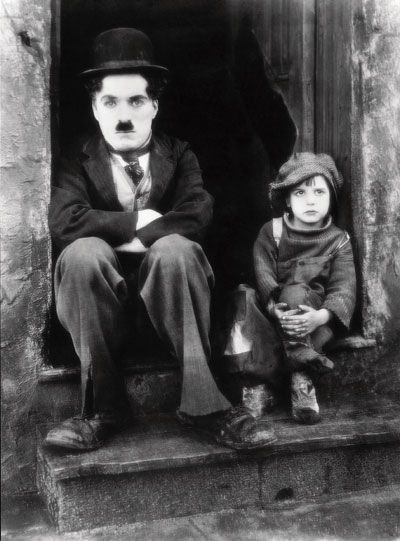

Charlie Chaplin's The Kid (1921)

12:00pm, Saturday, December 17, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$5 Admission for ALL!

Please bring a donation for the Calgary Food Bank

PG | 68 mins | English | B&W | 1.33:1 | 35mm

The very simple plot has the Little Tramp rescuing a baby on a doorstep (deciding to keep it to avoid attracting the attention of a nosy cop) and raising him for five years. At that point, officials attempt to take the child away. Critics at the time praised the film for its effortless combination of comedy and pathos, which is not as easy as it looks. Filmmakers today are still trying to come up with that winning combination and failing more often than not. The Kid's memorable highlights include breaking and selling windowpanes, Chaplin's fight with the neighborhood bully, and the truly bizarre dream sequence with the vampish fairy. The most famous clip is the one in which the kid cries and calls to Charlie from the back of the orphanage truck, and it's a truly stunning, heartbreaking moment. In the role, Jackie Coogan surely gives one of the all-time great juvenile performances, and for a while he became as big a star as Chaplin. … In the 1970s, Chaplin composed a beautiful new score for The Kid, and it's the one that's still used today. -Jeffrey M. Anderson, 2005

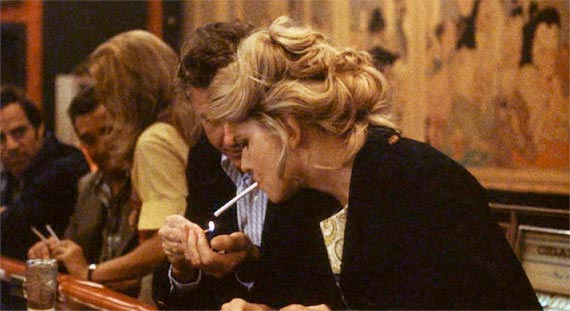

John Cassavetes' A Woman Under the Influence (1974)

7:00pm, Thursday, November 17, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

14A - Mature Subject Matter | 146 mins | English | Colour | 1.37:1 | 35mm

John Cassavetes' harrowing masterpiece charts the emotional meltdown of a suburban housewife and its effects on her blue-collar Italian family. Gena Rowlands stars as Mabel Longhetti, a mother of three whose husband Nick (Peter Falk) works as a construction worker; a mismatched couple like so many others in Cassavetes films, the Longhettis seem to be complete opposites: she's impetuous, extroverted, and fragile, while he's controlling, distant, and hard-bitten. Their differences underscore a series of domestic dramas, culminating in a nervous breakdown that sends Mabel to a psychiatric hospital for six months, only to return to a home environment on even thinner ice than before. The improvisational style central to Cassavetes' vision is at its most acute throughout A Woman Under the Influence. Like its title heroine, the film threatens to veer out of control at any time, its shape and scope defined not by narrative but by the emotional upheaval at its center. Embracing the full spectrum of the Longhettis' relationship, from seismic bursts of high drama to small, even trivial moments of domestic tedium, its long scenes relentlessly probe every nook and cranny of the family's life, drawing out each moment for maximum emotional impact; the film is by turns beautiful and ugly, illuminating and frustrating, and it features a performance by Rowlands as heartwrenching and unforgettable as any ever committed to celluloid. -Jason Ankeny, Rovi

Often crudely synopsized as "that movie about the crazy wife," the recently restored A Woman Under the Influence came about after Rowlands asked her husband, Cassavetes, to write her a role that would illustrate women's struggles in the modern age. From that slim notion, he concocted an epic relationship drama about Mabel (Rowlands), wife and mother of three young children, and her blue-collar husband, Nick (Peter Falk). Once we're introduced to this couple, we know them—he's a backslapping guy's guy, while she's … well, something is definitely off about Mabel. A little too loud at odd moments, a little too animated and temperamental, Mabel is a hoot, until she's not; her outsize personality isn't an affectation, but instead a sign of something more troubling. Nick's co-workers gingerly dance around the subject, but everyone knows: Mabel's a good soul, but she's not well.

Inspired by Rowlands's intense, unapologetic performance, Cassavetes isn't concerned with explaining Mabel's "condition" or creating an overt societal critique around it. Through extended, seemingly mundane sequences, this quietly feminist film simply presents the life of a working-class Los Angeles family with a nonchalance that amplifies Mabel's instability, but also normalizes her strains until they resemble the daily emotional fissures of any good mom. In retrospect, A Woman Under the Influence seems to anticipate the following year's Jeanne Dielman, which would express many of the same sentiments in even more shocking terms, but its shadow stretches even further. Compare Cassavetes's film to any number of more recent agony-of-suburbia dramas focusing on put-upon mothers—Julianne Moore's harrowing performance as the environmentally sensitive Carol in Safe, the suffering matriarchs of Little Children and Revolutionary Road—and you'll realize how these later films echo Influence's underlying conflict: the tension between mother as loving rock of the family and mother as human being, with inner turmoil. -Tim Grierson, The Village Voice, 2009

35mm restored print courtesy of the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Preservation funded by The Film Foundation and GUCCI.

Jean Renoir's The Rules of the Game aka La règle du jeu (1939)

9:00pm, Thursday, November 10, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG | 106 mins | French with English subtitles | B&W | 1.33:1 | 35mm

7:00pm, Friday, November 11, 2011

12:00pm, Saturday, November 12, 2011

w/ 'Film School' lecture & discussion

At la Colinière, the deceptively idyllic country estate of a wealthy Parisian aristocrat, a selection of society's finest gather for a rural sojourn and shooting party; over the course of the weekend, all of their worst behaviors unmasked, this cream of the idle crop reveal themselves to be absurdly, almost primitively, cruel and vapid. It took decades for Jean Renoir's The Rules of the Game to be recognized as a masterpiece, receiving negative reviews and even provoking near riots in Paris upon its release, in 1939, which resulted in Renoir cutting twenty-three minutes from the original version, and a subsequent ban by the French government. The original negative was destroyed during World War II, and only in 1959 was the film fully reconstructed from surviving prints and embraced by audiences and critics alike. Now, thanks to an unprecedented complete digital restoration today's audience can see the film as Renoir intended it to be seen originally. Playing with the lightest of touches, yet stinging like the greatest of tragedies, The Rules of the Game has come to be regarded as one of the greatest movies ever made.

The remarkable history of Rules of the Game

Part I, 1939–1959

No film of this stature has ever been received so harshly at a Paris premiere—yet more words have been written about Rules of the Game subsequently than any other film in the history of the French cinema. European film historians and directors alike consider Rules of the Game among the two or three greatest French films ever made, and their judgments are based on the only version of the film that has been available, mutilated and incomprehensible, from which thirty minutes is missing, including many essential developments. The French call it "le film maudit"—the film with a curse.

Renoir finished a skeleton treatment of Rules of the Game early in 1939, and , with several friends, set up a cooperative society to produce the film. Financing was arranged with considerable difficulty, but the production was announced as one of the most important and highest-budgeted of the year.

Troubles started with casting. Renoir had written the two leading roles with Simone Simon and Fernand Ledoux in mind—they had been paired in his commercially successful The Human Beast, and the actress was at the apogee of her fame. To everyone's chagrin, she demanded a third of the budget as her salary, and Renoir was obliged to look for a substitute.

One evening, at the theatre, he found her: the Princess Starhemberg (who later used the pseudonym Nora Gregor), an Austrian emigree with no previous acting experience and only rudimentary French. The Princess's accent and her great physical difference from Simone Simon necessitated a change in the casting of her husband, and the role went to Marcel Dalio, a happy choice for performance but one which led to some of the opening-night difficulties, since Dalio's Jewish origins were well-known and the film was violently attacked by the anti-Semitic press. The Princess's strong German accent added fuel to the flames of ultra-nationalism at a time when relations between France and Germany were at their lowest ebb.

On February 15, 1939, the entire cast and crew left for Sologne, where the exterior scenes were to be shot at the Chateude

La Ferte-Saint-Aubin. Two weeks of steady rain prevented any work on the film, and Renoir used the costly delay to work on his unfinished shooting script. The celebrated rabbit hunt sequence, which lasts only a few minutes on the screen, required almost two months of effort, and had to be completed by a part of the crew left behind when Renoir returned to Paris, where some of the costliest sets of the pre-war French cinema had been built. Mobilization among employees of the production crew slowed the work still further. When it was finally completed, the film cost far more than the original budget allowed..

Rules of the Game opened at two theatres in Paris on July 7, 1939, following the enormously successful run of John Ford's Stagecoach. Before the feature started, there was a short documentary devoted to the glories of the French Empire, with waving flags and long lines of soldiers—a paean to the pride of the French nation. Perhaps this unfortunately-chosen short subject had something to do with audience reaction to the feature. At any rate, never has there been such an opening night! The audience began to whistle almost from the beginning of the picture, and the whistling changed little by little to angry shouting. Soon almost none of the dialogue could be heard in the uproar. Some of the spectators began to tear up the seats, others made torches of newspapers; at the end of the pictures, demonstrations almost turned into a riot. Although everyone realized there was little to be done to salvage the pictures, it was twice cut after Marguerite Renoir had sat through several showings to learn which scenes caused the worst reactions.

The critical reception was hardly better; most of the newspapers called the film a betrayal of the glory of France. It was a complete commercial disaster, and in October the government forbade its showing because of its demoralizing theme. The German and Vichy continued the ban. The original negative was destroyed by bombs, and at the end of the war only a few copies of the twice-cut version remained.

Rules of the Game was revived after the war, mainly in film societies. The New York premiere, during a particularly hot summer in a theatre without air-conditioning, had predictable results.

In 1956, two young French cinema enthusiasts, Jean Gaborit and Jacques Marechal, persuaded the owner of the rights to sell them the film and all remaining material. By a stroke of luck, they came across an old letter which led to 200 boxes of film in pieces in a warehouse, miraculously untouched. With infinite patience and several years of painstaking work, they managed to reconstitute the original version with only one small piece of less than a minute missing: a conversation between Octave and Jurieu in which the former explains that what attracts him to maids is their ability to make conversation.

Part II, 1959–2006

As digital technology has become more advanced over the last twenty years the possibilities for film preservation have increased manifold. For The Rules of the Game, which, thanks to the careful reconstruction in 1959 was now once again complete, the quality of the existing elements still posed a problem. The 1959 reconstruction was created from a patchwork of footage, meaning that all new 35mm prints made from the reconstruction in the last 50 years echo the same flaws as the original (murkiness, inconsistency, scratches).

Thanks to the boom of digital home video, the technology has now appeared to remove these flaws through a complete digital transfer, but for The Rules of the Game it was still important to start with the best possible elements.

In the mid-1980's, Criterion—which specializes in restoring classic films and lacing them with scholarly commentaries—put Rules of the Game out on laser disc. Its picture quality, though superior to the 16-millimeter reels that most people had seen at art houses or college film societies, was unacceptable by the standards of today's DVD's: soft-focused, murky and way too dark.

The laser disc was mastered from a print of the film's 1959 reissue.

Today, for anyone serious about making DVD's, a film print is an inadequate source. The ideal source is the original camera negative. But the negative for Rules of the Game was stored in a French warehouse that was bombed during World War II.

If the negative is unavailable, the next best source is the 35-millimeter "fine-grain master," which is processed straight from the negative. The next best after that is a duplicate negative, which is made from the fine-grain master. A print is made from the duplicate negative. That's three generations from the original camera negative—a copy of a copy of a copy of the real thing, each copy looking less pristine than the one before.

When Peter Becker, the president of Criterion, set out to make a DVD of Rules in the summer of 2001, he knew he had to find a better source than a mere print.

His executive producer in Paris, Fumiko Takagi, learned that a French film lab called GTC possessed a duplicate negative—one generation closer to the original. Examining the lab's records, she discovered that it also owned a fine-grain master, made from a negative for the 1959 reissue—another generation closer. But nobody at the lab could find it.

For two years, she begged and cajoled them to look harder. Finally, she gave up. The duplicate negative looked pretty good—better than any existing copy, on video or film. So last June, Lee Kline, Criterion's technical director, flew to Paris to make a DVD from the dupe negative.

"It really bothered me that a fine-grain master existed someplace and we were going with something worse," Mr. Kline recalled. "But this was all we had."

Meanwhile, Ms. Takagi kept pestering GTC. Suddenly, last August, just after she'd given up all hope, the lab told her the fine-grain master had been found. Mr. Kline, who had finished his work and returned to New York, flew back to Paris to take a look.

"It wasn't awesomely better, like when they found the original camera negative for The Grand Illusion," he said, referring to another Renoir masterpiece on Criterion DVD. "But the difference was big enough to justify doing it over." "Hunting The Rules of the Game". -Fred Kaplan, NYT, 2004

After the release of The Rules of the Game on Criterion Collection DVD, the desire was still strong to see this film once again on celluloid and in theaters.

The Criterion Collection transferred the 35mm Fine Grain Composite Print that had been found in France to a high-definition (HD) digital video format called a D5. This D5 HD video was meticulously created on a system known as a Spirit Datacine at VDM laboratory in Paris, France. The audio source that was used was the original optical soundtrack. Full HD density correction was then completed at VDM to ensure that the film achieved a uniform clarity throughout, with Phillipe Reynaud, serving as Telecine operator (the individual who transfers film elements to video and performs color correction at that stage) and Maria Palazzola supervising the entire process. Then thousands of instances of dirt, debris, and scratches were removed using the MTI Digital Restoration System. Audio restoration tools were also used to reduce clicks, pops, hiss, and crackle in the soundtrack.

Those steps, however, only marked the first phase in the creation of the new print. In the summer of 2006, that same D5 HD master was subjected to three more months of careful digital restoration (to prepare for projection on larger screens) and used as the source to create a completely new 35mm film negative, the first in 50 years, by outputting the HD video master to projectable 35mm film. This painstaking, exacting work was completed at Post Logic Hollywood.

The new 35mm prints created from this negative are dramatically better than any existing copy of The Rules of the Game. The film has never looked as sparkling as it does today. -Cy Harvey, founder of Janus Films

Roman Polanski's Knife in the Water aka Nóz w wodzie (1962)

7:00pm, Wednesday, October 19, 2011

The Plaza Theatre 1133 Kensington Rd NW

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

PG| 94 mins | Polish with English subtitles | B&W | 1.37:1 | 35mm

Roman Polanski’s first feature is a brilliant psychological thriller that many critics still consider among his greatest work. The story is simple, yet the implications of its characters’ emotions and actions are profound. When a young hitchhiker joins a couple on a weekend yacht trip, psychological warfare breaks out as the two men compete for the woman’s attention. A storm forces the small crew below deck, and tension builds to a violent climax. With stinging dialogue and a mercilessly probing camera, Polanski creates a disturbing study of fear, humiliation, sexuality, and aggression. This remarkable directorial debut won Polanski worldwide acclaim, a place on the cover of Time, and his first Oscar nomination.

From Mr. Polanski's 1984 autobiography, Roman, published by William Morrow and Company:

Knife in the Water started out as a straightforward thriller: a couple aboard a small yacht take on a passenger who disappears in mysterious circumstances. From the first, the story concerned the interplay of antagonistic personalities within a confined space. Though stagey, the notion of isolating three people from the world lost its theatricality when the setting was a sailboat. I wrote a short treatment and soon signed a contract for my first film with Poland's Kamera [film production unit]

I didn't get very far with my first script collaborator, Kuba Goldberg. Then Jerzy Skolimowski appeared on the scene. A university student, amateur boxer and published poet, he was also a film school aspirant who happened to be visiting Lodz Film School for the two-week entrance exam. At my suggestion he took a look at what my previous collaborator and I had so far produced. Our duo became a trio. Skolimowski was a stimulating and inventive collaborator. He snatched every moment he could spare to help me develop the screenplay, toiling nonstop into the small hours while moths flew at us from out of the hot summer night. His contribution to Knife in the Water was a major one. It was he who insisted that the action, originally spread over three or four days, should be compressed to twenty-four hours.

When the script was finished it was submitted to the Ministry of Culture for approval. My expectations were at a fever pitch—preproduction had actually started—when the board rejected it on the ground that it lacked social commitment.

Some eighteen months later, sensing the political climate had changed, I decided to try again with the Ministry of Culture. I tinkered with a few scenes, adding some snippets of dialogue designed to impart a trifle more "social commitment," and this time the screenplay committee passed it for production.

Then I started casting. For the middle-aged journalist husband I settled on an experienced stage actor named Leon Niemczyk, who was handsome and slightly mannered in a way that suited the part. I originally intended to play the young hitchhiker myself, but I was eventually dissuaded. Any director making his first feature film was vulnerable to criticism of all kinds, so combined responsibility for screenplay, direction, and one of the three parts might lay me open to charges of egomania. Rather than court the hostility of critics, I eventually picked Zygmunt Malanowicz, straight out of drama school. Casting the journalist's wife proved more difficult: I decided to look for a non-professional. On the strength of a screen test, I gave the part to Jolanta Umecka, whom I spotted while prospecting at a municipal swimming pool in Warsaw.

Second only in importance to cast and crew was the large houseboat that became our floating home for several months in the summer of 1961. I insisted on renting this in the knowledge that it would make for greater efficiency and mobility while shooting, quite apart from being cheaper than score of hotel rooms.

Even discounting wind, weather and the natural hazards of filming afloat, Knife in the Water was a devilishly difficult picture to make. The yacht was quite big enough to accommodate three actors but uncomfortably cramped for the dozen-odd people behind the camera. When shooting aboard, we had to don safety harnesses and hang over the side.

After all the hardship endured in the making of my first film, the press showing was a disaster. The critics were determined to pan it. The members of Poland's nomenklatura (communist establishment) were starting to get rich quickly at this period, and Knife was, among other things, an attack on privilege. Whether motivated by spite or political zeal, most critics vociferously demanded to know what the film was about. My "cosmopolitan" background was grist to their mill.

Despite its rejection in Poland, Knife caused considerable stir elsewhere. It won the coveted Critics' Prize at the 1962 Venice Film Festival. The following year, a still from the film appeared on the cover of the September 20, 1963, issue of Time. Better than that, it was nominated for an Oscar in the best foreign film category. -The Criterion Collection, 1991

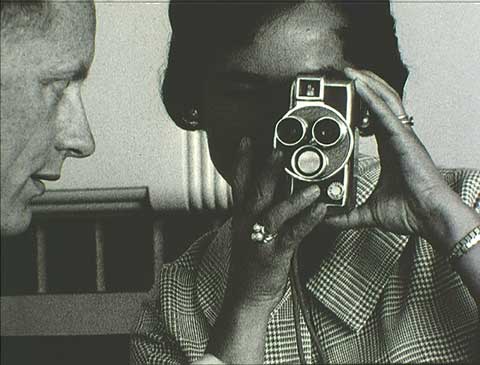

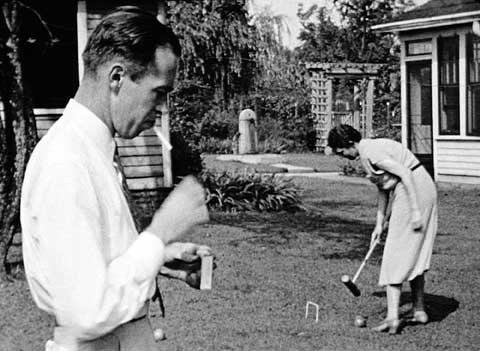

Dwight Swanson's Amateur Night (2011)

7:00pm, Thursday, September 15, 2011›

The Plaza Theatre›1133 Kensington Rd NW›

$8 Members / $10 Students/Seniors / $12 General Admission

83 mins | English | B&W,Colour | 1.37:1 | 35mm

Dramatic, funny, poignant and even strange, Amateur Night presents 16 amateur films from the collections of American film archives. Piecing together family moments, historical scenes, animation, drama, comic routines and travelogues dating from 1915 to 2005, this groundbreaking compilation demonstrates the eclectic array of entertainment, innovation and enlightenment found in home movies. Featuring films by average Joes alongside notables like Alfred Hitchcock, Richard Nixon, animator Helen Hill and Smokey Bear, Amateur Night adds to the images archival audio, commentaries from family members, as well as newly-recorded music. Blown-up from the original reels to 35mm, Amateur Night is a feature length big screen journey into the eclectic past of small-gauge filmmaking.

FULL SYNOPSIS

What do you think of when you think of home movies? Whatever the answer, chances are that it is mostly correct, but also incomplete. Amateur Night, a compilation of 16 home movies and amateur films culled from the collections of film archives is a journey into the eclectic past of home-based filmmaking. While countless filmmakers have incorporated home movies into their own films, this is likely the first feature-length film made up entirely of unedited amateur films, foregrounding them not as illustrative footage, but as complete works to be viewed on their own terms.

A mixture of excerpts and complete reels, the films are allowed to stand on their own with their occasional mistakes intact. The films come from a variety of sources, including 8mm, super 8, 16mm and the rarer 9.5mm and 28mm formats. Three films come with their original soundtracks (all narrations recorded by the filmmakers), while the remaining films have been supplemented with new tracks, including archival sound and music and newly-composed musical scores by 4 Five VI, an ensemble that specializes in innovative silent film accompaniment, and Rachel Grimes, formerly of the Louisville, Kentucky band Rachel’s. Five of the films include commentaries recorded specifically for the film by relatives of the late filmmakers, such as Patricia Hitchcock O’Connell, who shares memories of her father Alfred Hitchcock.

Family life has long been at the heart of home moviemaking, and it is represented here in many forms, including the Hashizume family in the Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming during the Second World War; the multiethnic life of Mort Goldman, a New Jersey chicken farmer; a comedic sketch by the Minnich family of Knoxville, Tennessee, and Alfred Hitchcock cavorting with family and friends at his country home in England.

Amateur filmmakers also covered historical events in their uniquely personal ways, such as an atomic bomb test in the Nevada desert, filmed by a Georgia newspaper man; footage of Richard Nixon’s visit to Idaho Falls in 1971, filmed with a degree of intimacy that only his staff members (armed with a super 8 camera as they looked over his shoulder) could manage; the Last Great Gathering of the Sioux Nation, filmed in Nebraska in 1934; and the late filmmaker Helen Hill’s portrait of her beloved New Orleans, shot during her return following Hurricane Katrina.

Amateur Night includes not just raw home movies, but also examples from some of America’s most talented amateur filmmakers, including the National Film Registry title Our Day, a finely crafted portrait of life in small town Kentucky; Fairy Princess, a charming movie by award-winning Chicago filmmaker Margaret Conneelly, combining live-action sequences and pixilated animations; and Welcome San Francisco Movie Makers, a portrait of a filmmaking club from 1960.